Two weeks after the event, the Isle of Wight Festival is beginning to feel like a memory, blurring at the edges. It takes on the magic of distance, but at the expense of the vividness of detail. It is a process of solidification, a drying out: experience fades as a side-effect of the preservation of memories.

This Festival was particularly special for us: an unexpected treat and a freebie. We had not intended to go. Back in 2008, 2009 and 2010, the Isle of Wight Festival was a part of our courtship, but it became an expensive chore: too costly; too hectic; too like a Friday night in an alcohol-fuelled high street circa 1999.

For two years, we went to the Latitude Festival with my sister and her family. When I was made redundant that became a treat we couldn’t justify, but I know that Amanda regretted missing it. We had seen some wonderful art there, and enjoyed some special experiences: she and my brother-in-law throwing themselves into the crowd when The Levellers played a mini-stadium in a wooded amphitheatre; being surprised and delighted (and relieved) when Adam Ant’s comeback was a joy, rather than the embarrassment we feared; a gig by Dexy’s that was part musical theatre, part crowd-pleaser; John Shuttleworth doing Two Margarines on the Go; Benjamin Zefaniah, amazed by the rapturous audience that filled the poetry tent for his performance.

The moment that stood out for me, though, was at Latitude 2012, in the poetry tent again, when Mark Grist’s1performance of A Teacher, Eh? moved us both to tears. I am really just a casual reader of poetry, and I think that was the first time in my life that a poem made me cry. Later, Amanda told me that wasn’t her favourite: she’d seen him the previous year, and was waiting for Girls Who Read.

Anyway, he made an impression. When I got home, I searched for him and found some of the rap battles that had won him a notoriety most poets can only dream of. At the time, I was working in a prison, and was surrounded by rap: I knew some of the crews and a little of the context of spoken word music in London at the time. I had a standard lesson based on how rap was distinct from poetry (a sneaky way to teach metre). I loved the way Mark Grist subverted the subversive, using poetry to undermine the pomposity of rap without dismissing its vitality and beauty – taking on the boastful cardboard masculinity; the sexist, homophobic adolescent violence, and working in a positive answer to what I kept hearing in my learners’; rhymes: the underlying despair.

In February this year, Mark played a poetry group on the Island: Reading Between The Lines, organised, hosted and made unique by the very lovely King Stammers2, an Island character and poet. Outside, after the event, having scaffed a cigarette from an innocent bystander, I babbled some appreciative nonsense at Mark as he left the venue. He’d done a good gig: funny and moving, and not acted like the big star lording it over the amateur local poets, but had complemented their performances, varied as they were. I recognised the instincts of a good teacher, and a good man.

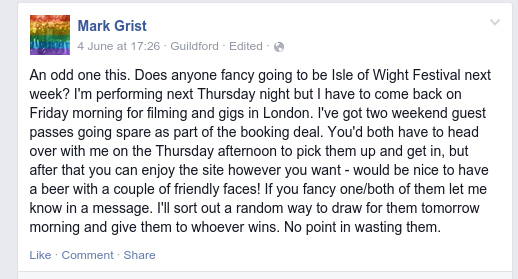

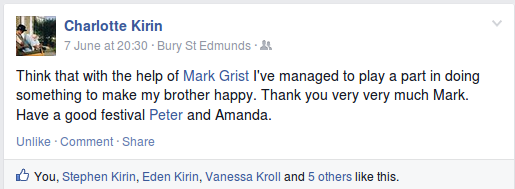

Then, early last month, this happened:

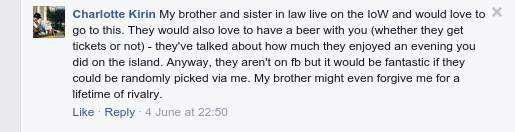

I rapidly joined Facebook and posted this:

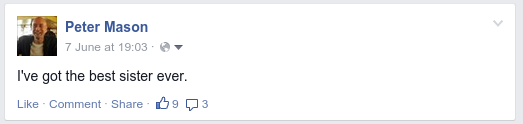

Which earned this reply:

Our life had been complex for some time, and we were both a little blinded by the fact we suddenly had something to look forward to. I remember Amanda saying, “Something good’s happening!” and I knew exactly what she meant. She works away during the week, so the organisation was a bit three-way, but I found myself talking to this person who had, so far, been a ‘figure’ rather than an individual, and he was really easy-going. It made sense for him to stay in our spare room and for us to drive him down to his gig, and that’s how it worked out.

Thanks to his being an artist, we got an extra armband each, which was a bit of a boost. It meant we could park in a separate car park, from which we got a mini-bus down to a tented bar where beer was normal-expensive, instead of festival-expensive, and where there were sofas and carpets and loos that had wash basins. It also meant that lots of lovely, full-of-life-and-more-excited-than-puppies-when-you-get-home young people, who couldn’t believe their luck to be working at a music festival, were available to help and guide and just be incredibly nice to us. Over the weekend, that tent was our base and turned what could have been a bit of an exhausting ordeal back into a pleasure.

For all the staff’s gorgeousness and loveableness, the bookings side of the festival, for the ’boutique’ (non-headlining) acts, was a bit of a shambles. It was up to Mark to work out where he was playing and when: the staff really didn’t have a clue. I downloaded the festival app and we established where his first set was, and told the staff who, loveably, arranged a lift for us on a golf buggy. Amanda sat in the front with a loveable puppy, and Mark and I perched on the back, enjoying the broken suspension on every bump.

He was a little intimidated by the Bohemian Woods stage: It was a reasonably large amphitheatre, and there was a rock band playing to a decent sized crowd when we got there. We sat and had a few minutes behind the stage and then he went to get on stage, we went round to the front, and in that time, people turned up. Lots of people: a hundred or so people.

And this is the surprise, for someone who doesn’t often go to poetry events: poetry is very, very popular. Mark’s nerves seemed to dissipate with the first cheer to something he said, and he performed for about thirty or forty minutes to an engaged, cheerful, cheering audience. He did the story of becoming a teacher in Peterborough, of being poet laureate of Peterborough and the challenges that entailed. He told the story of defending the most excluded and disengaged students from a further, disastrous exclusion, and how they blackmailed him into doing his first rap battle. He did I’m Really Good at Board Games and he did A Teacher, Eh? He didn’t do Girls Who Read.

The way he talks about teaching is very story-oriented, and he plays it up for laughs, but the real instincts of stage craft, that draw on that teaching skill for his techniques of engagement, and also for his deep-down passion and regard for other human beings, are, I think, rooted in the fact that he taught people who did not want to be taught, and pursued the hardest part of teaching: being on your students’ side.

This was most visible after the gig, when he talked to people who approached him, some of whom he knew and some who simply knew him from YouTube. He was anxious to get to the next venue, and the loveable puppies were not hanging around Bohemian Woods, so we didn’t have anyone to ask. We knew he was due on in only a little while, but he engaged and was humorous, and, when a young man began to recite some poetry to him, he became utterly focussed, waving away my warning about time, listening studiously and responding with absolute positivity. I wasn’t able to hear the work, but I wish I had.

We had a mad dash through the festival crowd, looking for a place called The Champagne Bar, which didn’t bode well. It was an over-priced tent with a casino attached (I don’t think it was for real stakes, but don’t know) with a drinks garden outside, guarded by security men. You could only get champagne or Prosecco and you couldn’t take your own drinks in. Next door to it was a Tia Maria camper van with a DJ booth playing generic remix dance pop.

Again, no one knew anything, so we checked the guide, and he got up onto the little booth/stage inside the tent at the appointed time. This time, he didn’t do his standard spiel. Thanks to the size of the venue, he was able to reach out to the audience very quickly. A slightly suspicious crowd, with some people who had come to the venue to see him, but a lot of people who were just there because they are champagne bar sort of people, was won over by the opening lines of the first poem: he gave the audience the choice of a poem about work or a poem about a dog. No contest.

His second poem was a technical exercise, written with only one vowel. It was curiously formal for Mark; something of a departure and it felt, to me, like a portfolio piece. He also did a poem about drugs that held the crowd in embarrassed empathy: it’s called Nutmeg, and is about a middle class rite of passage we all try to edit out of our memories. The next poem he performed was a depiction of a lairy lager boy trying to pick up your friend in a club, boasting about how hard his mate, Daryl, is and side-lining and ridiculing you in his attempt to impress her, while getting more angry and more rapey as his amorous failure becomes clear. I thought it was a powerful piece of spoken theatre, and it reminded me of some of the young men I taught in the prison, utterly unable to get their heads round the idea that what they wanted might not be a moral imperative to others. Later, as we bought cigarettes, Mark said he worried about that poem; that it was “classist”, and I almost laughed, in the light of the poem he did next: The Hottest of All The Gingers. If any of his poems are likely to give offence, a poem that refers to munching on cinders, cunnilingus and strawberry blonde curls peeking from thongs is the one. Incidentally, this poem has, I think, my favourite opening of any of his works.

He finished, at the request of the young woman to whom he’d addressed Gingers, with Girls Who Read, and I got it. It’s a woman-magnet of a poem: a heart stopper for women who didn’t get out and about as teenagers; women who came into their own at university. I looked round, and men were listening happily enough, but the women in the crowd, Amanda included, had a look you see on the faces of suckling cats: a contentment that transcends earthly pleasure, and bodes very, very well for the man who can inspire it.

Amanda wanted to see Billy Idol, so we walked up to the Big Top, stopping to buy Mark some cigarettes on the way. He was recognised several times and was courteous and patient. We settled outside the tent: I would not have gone into that crowd for anything, and Mark had met some friends from the Champagne Bar who he knew from the ‘circuit’. They were charming. I acted as photographer, and my contempt for iphones was confirmed: they have a second’s delay before making a picture which makes judging a shot impossible.

Amanda joined us, and we enjoyed a small gathering for half an hour or so. At one point, a young man, clearly enjoying something other than nutmeg, approached Mark and asked him to bust some rhymes. He refused, but recited a haiku. It was a good joke, but I won’t write it up. I suspect he uses it as a fallback and I don’t want to spoil that.

Mark had been tired when he arrived on the Island. By this point, he must have been exhausted. We walked up to the car park, through a perfect English summer night, talking about his extraordinary life and his plans. Already, the festival site, its routes and neighbourhoods, felt settled into the landscape, as though they would always be there. We walked unconsciously, lost in our conversation: Amanda, as she often does, became a gentle inquisitor, encouraging Mark to talk freely about his hopes, his plans and his frustrations. At one point, he said he wanted to be a bard; a street magician, and the reference was a shared compass point. The noise of the music behind us was like another world; a strange, persistent, but meaningless activity; as undemanding as a temporary friendship, and as magical.