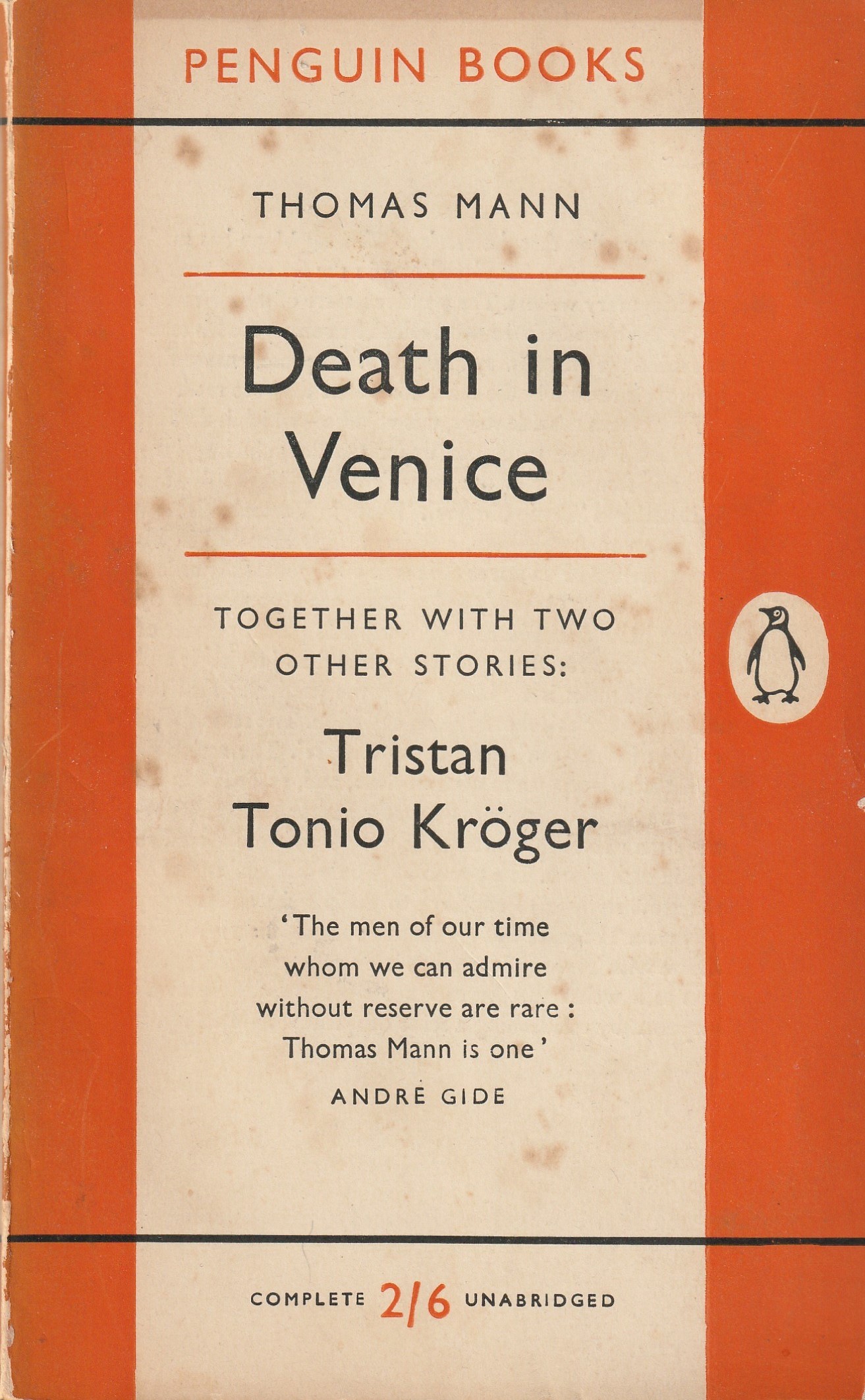

I wrote about Thomas Mann in a recent post1 and recalled that I had read Death in Venice many years ago, but remembered little about it. I searched the house, but couldn’t find a copy, so I looked on ebay. I might have had a modern copy for under £2 but this one was available for a fiver plus postage. I am enough of a book fetishist to love old Penquins and when it arrived I was rewarded with that smell that is one of the most profound yet fleeting sense experiences: the smell of an old book as it is opened for the first time in a long while.

This copy did not betray any secrets with it. Often, books of this vintage come with the scent of tobacco mixed in with the paper-and-ink must; once or twice, enticingly, I have opened a book and had a hint of Chanel No. 5, triggering images of a languid reader in a Chelsea flat. More common are the suggestions of student reading: sandalwood or patchouli, or the faintest gust of weed, along with a wine stain or two. But, no; this book just smelt of its constituent parts, and did not even carry an owner’s inscription. Its past is a closed book.

Having reread it, that blankness seems wrong, for Death in Venice, though it is written in a voice that is, initially, detached and calm, is a story of intense passion and of a slide into madness. It is very much more vivid than I remembered and what really surprised me about it was the baroque tone of degraded magic. Despite being introduced as the perfect bourgeois rationalist, whose life is an ordered triumph of will and detachment, Aschenbach voyages through a vivid world of encounters with the grotesque to meet his lonely, perverted fate. The uncanny element is introduced in the vision of the stranger outside the mortuary chapel in Munich, after which Aschenbach conceives his plan to leave his well-ordered life for a few months of restorative travel. It is developed in various encounters on his journey to Venice, through the ticket agent, the old drunken reveller on the steamer, the unlicensed gondolier and the manager of the hotel, “…a small, soft, dapper man with a black moustache and a caressing way with him…”.2 It reminded me of the sense of uprooting that launches Marlow’s journey into the interior in Heart of Darkness, although that is another book I haven’t read for decades, and may be misremembering.

The oddness that seems to clamour around Aschenbach as he travels is heightened by his character. In the early pages, he is established as a prissy old maid, both stuck up and over-sensitive, who manages his squeamishness by controlling his surroundings. Mann describes this nature and its tendency towards paranoia in beautiful terms, worth quoting at length.

A solitary, unused to speaking of what he sees and feels, has mental experiences which are at once more intense and less articulate than those of a gregarious man. They are sluggish, yet more wayward, and never without a melancholy tinge. Sights and impressions which others brush aside with a glance, a light comment, a smile, occupy him more than their due; they sink silently in, they take on meaning, they become experience, emotion, adventure. Solitude gives birth to the original in us, to beauty unfamiliar and perilous – to poetry. But also, it gives birth to the opposite: to the perverse, the illicit, the absurd.

((Ibid))

And so, as the central non-relationship of the story emerges and Aschenbach’s passion for the boy Tadzio unfolds, his perversity does not seem as strange, jarring and ugly as it should. Aschenbach has already developed a seedy quality, reflected in his experience but also in his prissiness and impatience with others. His tendency to be disgusted by and dislike people is the other side of his capacity to idealise and intellectualise this objectified stranger. I mentioned in my earlier post that…

I remember feeling slightly alienated by the conflict between the internal values of the story – an ambiguous mix of social self-criticism and moral reverie – and the actual sleaziness of the character, engaged, after all the angst about aesthetic ideals, in a lust which is the deepest crime of modern culture.

I hadn’t remembered – or, perhaps, as a younger reader, I didn’t pick up on – how the aesthetic moralising degrades as Aschenbach’s obsession takes him over. This story is a quite clear parable of the fragility of bourgeois restraint. Nothing Aschenbach does is truly alien to him: in true early-twentieth century fashion, Aschenbach suffers a collapse of repression.

Even before he has let his passion take hold, the sickliness of the environment is pre-signalled in his discomfort with the climate. He attempts to escape, but is relieved when his plan to leave falls through and, realizing when he next sees Tadzio that the boy is the reason he wanted to stay, he is, from this point, lost to his obsession. Before then, he still holds on to the forms of his intellectual conceits, “…assuming the patronizing air of the connoisseur to hide, as artists will, their ravishment over a masterpiece.”((Mann, p35))

The sense of the uncanny has, by now, become monstrous, and is given a form in the growing awareness of the cholera outbreak which is threatening Venice. Aschenbach attempts to find out the truth about the epidemic, but seems also to lack the will to do anything about it, as he is lied to and soothed by the hotel manager, a street performer and the barber. However, when the young English clerk in the travel bureau whispers the truth to him, Aschenbach cannot turn the knowledge to action:

…the thought of returning home, returning to reason, self-mastery, an ordered existence, to the old life of effort. Alas! the bare thought made him wince with a revulsion that was like physical nausea. ‘It must be kept quiet,’ he whispered fiercely. ‘I will not speak!’

((p75))

A dream follows; a nightmare of orgiastic pagan savagery, after which, it is clear that Aschenbach is ill. The magic has become the detached ecstasy of low-grade fever, in which internal experience entirely overwhelms the outside world. He seeks to remake himself with cosmetics, with the help of the barber, who contrives to transform him into a grotesque as alarming as the drunk on the steamer:

There he sat, the master: this was he who had found a way to reconcile art and honours; who had written The Abject, and in a style of classic purity renounced bohemianism and all its works, all sympathy with the abyss and the troubled depths of the outcast human soul…whose renown had been officially recognized and his name ennobled…There he sat. His eyelids were closed, there was only a swift, sidelong glint of the eyeballs now and again, something between a question and a leer; while the rouged and flabby mouth uttered single words of the sentences shaped in his disordered brain by the fantastic logic that governs our dreams.

((p80))

Aschenbach’s final reverie is on the power of the passions that an artist must channel and repress in order to practice his arts. “…we poets cannot walk the way of beauty without Eros as our companion and guide.”((p80)) It is a complete reversal of the values he seems, at the opening of the story, to embody: an indulgent embrace of sensuality over learning, rejecting knowledge in favour of beauty:

For knowledge, Phaedrus, does not make him who possesses it dignified or austere. Knowledge is all-knowing, understanding, forgiving; it takes up no position, sets no store by form. It has compassion with the abyss – it is the abyss. So we reject it, firmly, and henceforward our concern shall be with beauty only. And by beauty we mean simplicity, largeness, and renewed severity of discipline; we mean a return to detachment and to form. But detachment, Phaedrus, and preoccupations with form lead to intocication and desire, they may lead the noblest among us to frightful emotional excesses, which his own stern cult of the beautiful would make him the first to condemn. Yes, they lead us thither, I say, us who are poets – who by our natures are prone not to excellence but to excess. And now, Phaedrus, I will go. Remain here; and only when you can no longer see me, then do you depart also.

((p81))

He seems here, to me, to be prefiguring his death. “I will go now,” means not just that he will finish the dialogue, but that he is aware, on some level, that this is the end for him. He is held to life only by his passion for Tadzio, but within a few days, he learns that the boy’s family are finally leaving.

The close of the story is magnificent. Aschenbach’s death is the central event, but, at the point before he finally collapses, a tableau plays out on the beach between Tadzio and his friend Jaschiu; a fight that seems to represent the collapse of their holiday friendship. Tadzio, humiliated, shrugs off Jaschiu’s attempts at reconciliation and retreats to the sea. The narrative voice never leaves Aschenbach; we see the boy’s isolated sulk through the eyes of the dying man, but, for half a page, the boy becomes a character rather than a figure, and the sense of the end of childhood and the clouds of approaching adolescence are drawn in the simplest description. He might have noticed the strange old man who has been making him uncomfortable over the previous weeks, but he is just a part of the cloudy, oppressive end-of-summer sorrow into which he has been plunged. For Aschenbach, however, the boy has acknowledged him, and legitimized his lechery.

It seemed to him the pale and lovely Summoner out there smiled at him and beckoned; as though with the hand he lifted from his hip, he pointed outward as he hovered on before into an immensity of richest expectation.

((p83))

And then, the end, unmourned by the reader, barely noticed by the love object, but,

…before nightfall a shocked and respectful world received the news of his decease.

((ibid))

- Politics, by W.B.Yeats [↩]

- Mann, T. trans. Lowe-Porter, H., 1955. Death in Venice. London: Penguin, p29 [↩]