Four months ago, almost to the day, I didn’t feel right on a Sunday morning. Amanda thought I was faking it, because it was the day of her father’s birthday celebration tea, and I might have been a little unenthusiastic about the prospect. Her doubt was good, though, because it allowed me, after my blood test results showed I was having a heart attack or, more correctly, a myocardial infarction, 1 to text her from Accident and Emergency saying, “I told you I was ill,” which was a great, great moment, almost worth having a heart attack for.

The realisation that this was serious seemed to come in little slides, rather than a tumble. The first sign was when a nurse practitioner, a former learner of mine and someone I like very much, went from friendly to grave, about half an hour after my blood test had been taken. An enzyme, troponin, was seriously raised, and Russ’ manner became serious and cautious, and he began to choose his words carefully. Later, while I was sat in a crowded A&E admissions corridor, a registrar came to me after my second set of blood tests and said they’d be finding me a bed fairly soon. He didn’t disguise that there was urgency: they had a certain amount of time to prevent further damage to my heart. I felt as though I was on a cliff edge, the words “damage to your heart” hammering at my balance. I had visions of no more cycling, of oxygen bottles, of short, halting steps in slippered feet, holding on to walls.

“We don’t expect this sort of condition in a person as fit as you,” he said.

Besides the troponin levels, I had very high cholesterol.

“I’m vegan!” I said, and I heard what became a refrain: some people just have high cholesterol. That seemed inadequate, to me. I didn’t have high cholesterol ten years ago, when I had blood tests as part of my registration with my G.P. practice. I don’t eat a lot of processed food. Could it be stress?

“Stress can be a factor,” they said.2

There was no room in the Coronary Care Unit, so I was moved to the Acute Care Unit, which is the place where ambulance arrivals are seen. It is not a good place to be put: it means you need immediate help but the specialist ward is too busy for you. I spent a sleepless night in a cubicle as emergencies came in, and as crash teams saved, or failed to save, people much sicker than me. The drip they put me on raised my blood pressure and gave me a headache. I was on half-hourly tests, so couldn’t sleep, and the constant alarms of blood pressure and cardiac monitors made a peal of electronica, one always out of time with another, like a round sung by a soulless robot choir, singing without listening, staring blindly ahead, their brittle harmonies drowning out their desire to scream.

At dawn, a consultant, reassuringly middle-aged, Asian and bearded, with a smiling gravity, told me that the CCU was unlikely to be able to take me so they were talking to The Queen Alexandra Hospital in Portsmouth about transferring me there. I asked how I was to get there and he said they’d take care of that.

The night shift left. The man with COPD in the booth next to mine was wheeled off, every breath a fight to the death, exhaustion and fear warring in his own personal hell. The day shift came to familiarise themselves with their patients but otherwise the hours dragged on into mid morning in uncertainty and exhaustion. The tea trolley lady got used to my request for soya milk in my tea, and the health care assistant got permission for me to stand up so I could use a bottle. I had established a routine.

Towards lunchtime, they were suddenly there. A registrar came and told a health care assistant to get me ready, and then an ambulance crew, a woman my age, and a younger woman, appeared with one of those tank-like, high-tech stretchers. I was strapped on, my possessions were perched on my lap and we were off.

The older woman, a paramedic, was leading the stretcher, so I was looking at her. I asked her how I was crossing the Solent.

“Hovercraft,” she said. “We’ll be coming with you.”

I was loaded into the back of their ambulance and attached to the heart monitor. She checked that it was saying I was alive and then she gave her colleague the all-clear and we were on our way. We chatted as we travelled to Ryde, and she told me that the hospital would have commandeered a hovercraft and the passengers would have to wait for the next one.

“It’s quite an honour,” she said. I thought, it’s a sign that I’m not in a good way, but I didn’t say it. Instead, I said,

“How much do you think that costs?” and she said, “Less than the air ambulance.”

I told her that I was friendly with Russ and that he was studying to become an advanced practitioner and she said that she was lined up to do that, but had deferred because it was her son’s GCSE year. Then she told me that she dreads the hovercraft – she gets seasick.

We arrived at Ryde seafront and they opened the back, but the hovercraft was still disembarking the passengers from the trip over so I lay looking out of the back doors of the ambulance, feeling exposed. The ambulance crew were busy removing bags and equipment from their vehicle, piling it ready to go aboard as soon as they got the signal.

I apologised to the hovercraft crew, but it seemed they enjoyed these situations. A young woman among them had done the course on safe stowage of a stretcher, and directed two men. They worked with cheerful speed, and she checked each of the buckles before giving the pilot the go ahead. I hadn’t been on a hovercraft for many years – it goes to Portsmouth and I prefer to travel via Southampton – and I’d forgotten what an odd sensation it is. It feels like a horse that’s rushing ahead. On that day, it was a horse running over very rough ground, pitching up and down. It’s not like a boat, though: you don’t crash down, but can feel that you’re cushioned. I was facing the stern, strapped into a bed, but I’ve always been a reasonable sailor and I was quite happy, trying not to enjoy the poor paramedic’s distress too much.

We landed at Southsea, and I was wheeled out into a grey afternoon, to another waiting ambulance, with a new crew. These were two young women, and the one who stayed with me in the back was newly qualified, still excited by her job. After a quick debate, they decided they were justified in using the blue lights, and we edged and shouldered our way through Portsmouth’s permanent rush hour towards Cosham.

I expected another crowded ICU and another long wait to be admitted, but they wheeled me through the hospital, into a lift and straight on to a rather luxurious ward. It was a large lobby ringed by single-patient rooms. In the middle of the lobby was a large nurse’s station, looking like the flight deck of a very smart space ship. Two nurses, both male, both young, both handsome and bored, with an end-of-shift distraction, introduced themselves and took me off the ambulance crew’s hands.

The two nurses finished their shift within the hour, and were replaced by an African nurse. I wanted to sleep so badly, and seemed to fall into it, but I was still on half-hourly observations, so was dragged up to wakefulness by this gentle-faced carer throughout the night. It prompted a chaos of dreams, vivid as fever wraiths. To me, it was a relationship, lived out in the echo-realm of faery, sad and lovely.

In the morning, I had to negotiate to have my bowel movement in a proper lavatory. I was not using a commode. I was ashamed by the attention, and annoyed with myself for being so precious. I had a shower and some breakfast and felt better, the strange, distant, fantastical night melting away as I interacted with ward nurses, an angry cardiology trainee who took an echocardiogram – I managed to calm her a little and get her talking about her course – and the Latvian cardiac rehab nurse, who gave me lots of useful information about my condition and was keen to reassure me that I would be able to have sex again.

I thought she was presuming rather a lot, but it was fun listening to her say “intercourse,” in her lovely accent.

I spent a week in hospital, waiting for a slot in the angio lab to come free. After that first, busy day, I was moved to a ward with four beds, and greeted by the other occupants as a welcome distraction. Over the morning, we got to know one another, in that slightly exaggerated blokey way that British men adopt with new acquaintances. Opposite my bed was a man in his late thirties, squarely built and with the air of perilous affluence of a hard-working business owner. He turned out to be a kind, gentle man, though worried about his business, a furniture retail warehouse, which was in the hands of a less interested brother and a couple of staff. His wife, a lovely woman as rotund as him, visited every day and brought him heart-ruining Pakistani delicacies. I liked him at once.

On my side of the room, the other occupant was an older man from the Island, a farm worker, who was waiting for a bypass. This is the hard core patient. Our businessman friend and I were both waiting for stents, but if you need a bypass, you are in serious need. Southampton doesn’t do bypasses – they’re less common these days. He was waiting for a transfer to, I think, St Bart’s, in London. He’d been waiting for a week and was, it became clear, slipping into depression. He hadn’t had any visitors in all that time. The businessman was trying to keep him cheerful, but there was an air of gloom about him that felt dangerous.

Our final comrade had loads of visitors. He was a man in his sixties who, I gradually gathered, was quite autistic. He spent a lot of time colouring, and discouraged conversation. I never established what his condition was, but his sister, who spent every afternoon with him, seemed cheerful.

After two days, I was moved from there. I was, a nurse told me, stabilised. There was no more danger of heart damage and I was now only in hospital for a stent. Unfortunately, each day’s list got hijacked by emergencies, and as you stabilised, you became less urgent and were dropped down the list. The businessman had his and came back to be discharged at around the same time as I was moved to the Cardiac Day Ward. The name was out of date. It was supposed to be an outpatients’ ward but is routinely used for inpatients in the angiography queue.

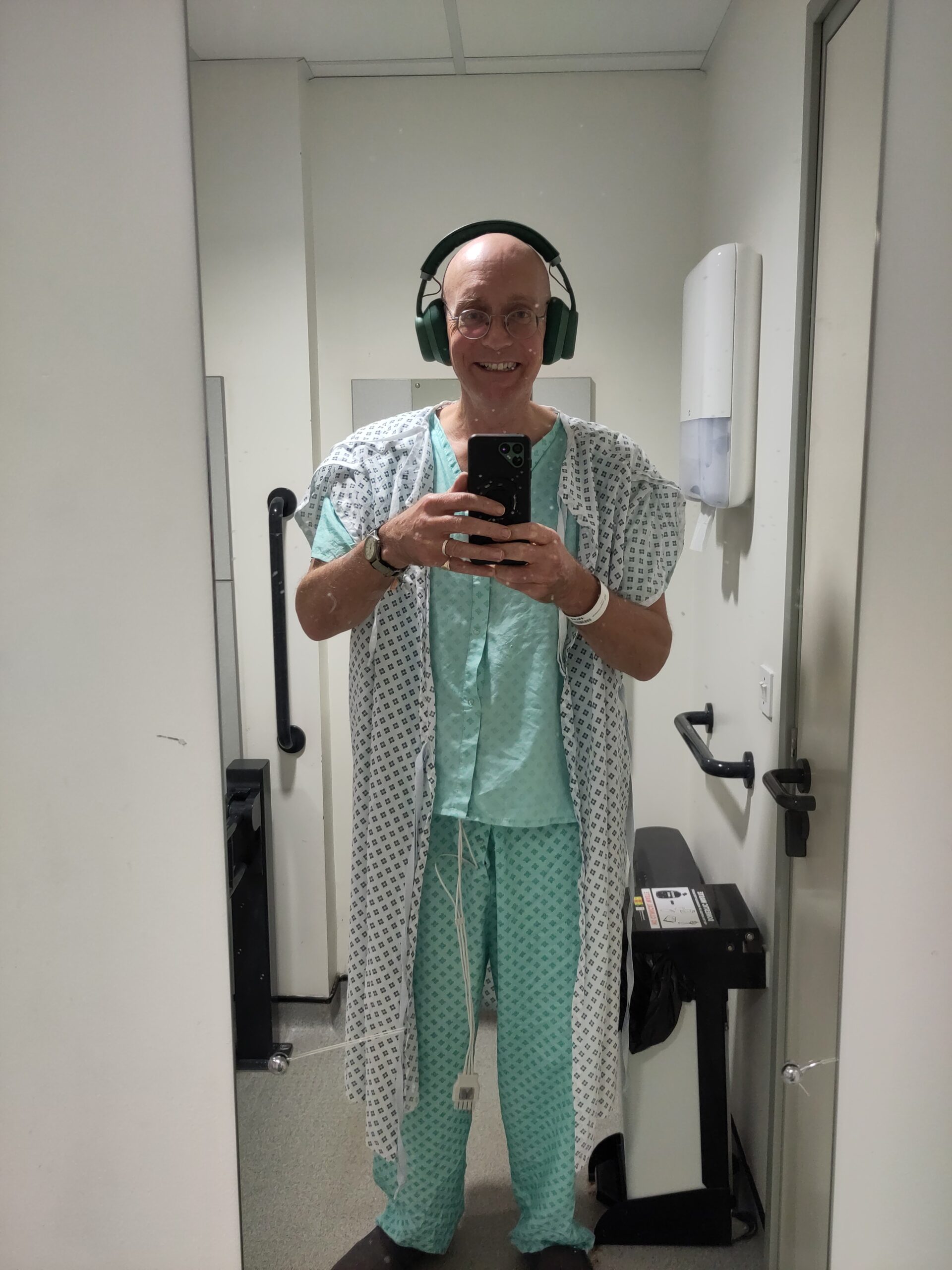

This was a long ward with one row of beds, each cubicle curtained and separated from its neighbour by a high, narrow window. Somebody had missed a trick and the windows were rectangular, rather than arched, which would have made the place feel magical. I was in the first cubicle by the main door. It became a home, and I would have defended it if they had tried to take it away from me. Each morning I was woken by a tired night nurse for my observations. I would get up after that and shuffle along the dimly lit room to the bathroom, to shower and shave and clean my teeth in leisurely peace before it got busy. I hadn’t packed pyjamas, so I was in hospital P.J.s, using a gown as a dressing gown. I looked like a very camp jedi.

The tea trolley was my main delight. They were initially thrown into confusion by my request for soya milk but became used to it and made sure there was always a mini pack of bourbons (vegan) among the biscuits. I heard about relatives who’d had heart attacks, their recoveries or, hilariously, given the setting, their failure to recover. I shared dog pictures with one of the housekeepers.

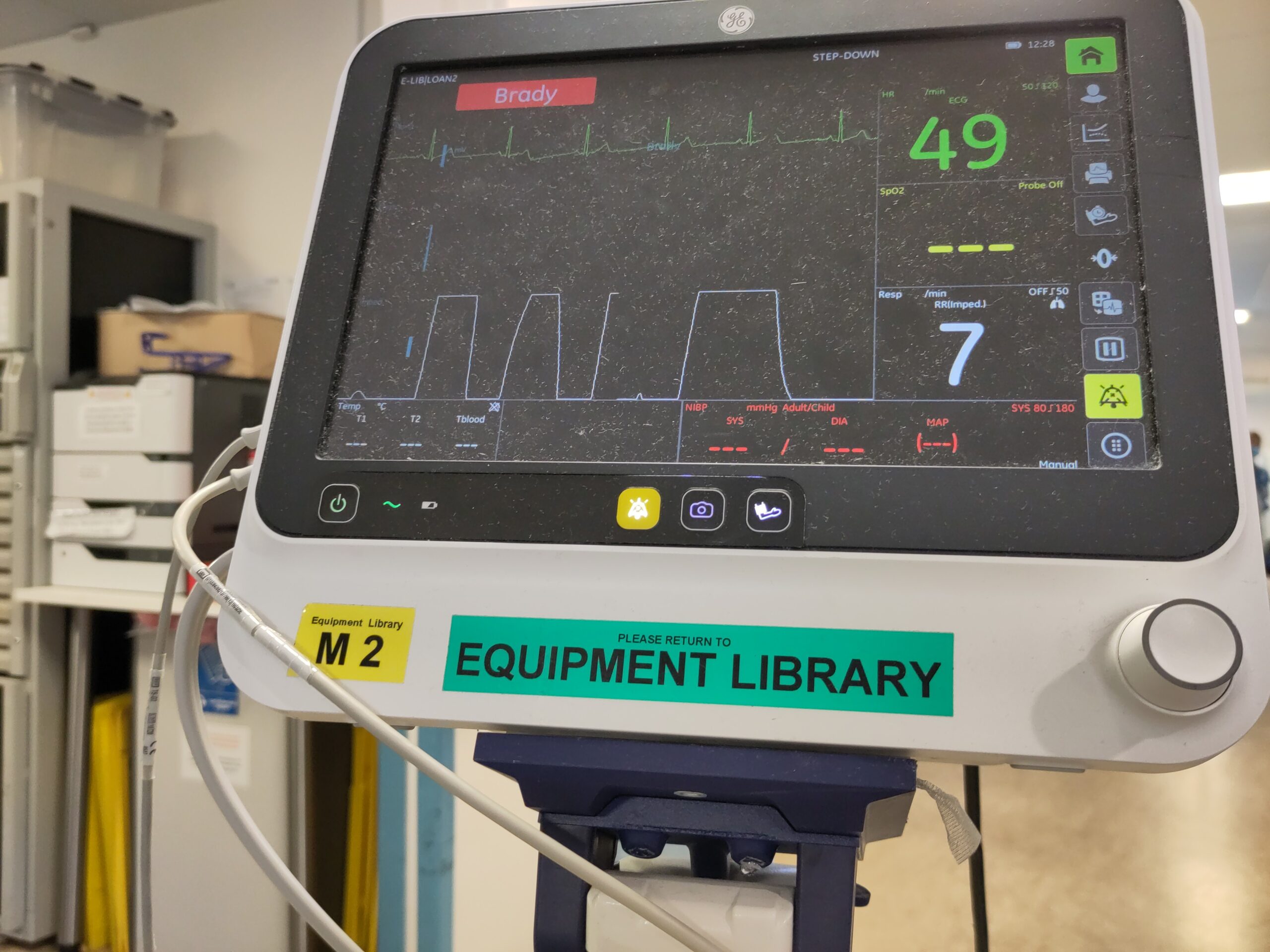

I got used to taking pills and to being connected to a heart monitor. I became adept at removing the clips without disturbing the stickers when I wanted to go to the loo, and replacing them when I returned. I had bloods taken by lovely nurses from various African countries, from the Philippines, from India. I tried to befriend each one, treating the brief interaction as a challenge and a respite, surprised that in such a busy place, I could feel quite so lonely. I became a connoisseur of cannula inserts.

Each morning, the consultant, who did his best to be patient and nice, came round to tell us that we were number one in the queue, number two in the queue, etc. Above number three, you stood a chance of having the procedure that day. Otherwise, you would be stuck until the next day. I tried my best to not show impatience. I was still effected by the night in St Mary’s Emergency Admissions ward, where I had listened to people die. I didn’t want to be in competition with people on the edge of death, when it was clear that I would live, would cycle again, would be okay.

Eventually, on the Saturday afternoon, I was taken in to a cave-like room, part laboratory and part Alien-film spaceship bridge, and put on a weirdly technical chair while filaments were pushed up my arm and a stent was fitted into my aortic artery. There was rock music playing softly: the Spotify playlist of someone who is proud of their taste. Surgical lights lit patches of the room, while the rest was lit only by computer screens and video monitors that showed the inside of my circulatory system, but were angled so I couldn’t properly follow the procedure. The Consultant asked me questions, but was impatient with imprecise answers and did not answer my enquiries. I guess he was doing overtime and, I suppose, concentrating. I’m grateful, but that sense of estrangement from control of my own circumstances is something with which I have become familiar since then. At the time, it annoyed me.

I left hospital the next day. My sister-in-law, Jo, and her partner, Paul, very kindly came to pick me up in their comfy S.U.V. and we got the Fishbourne ferry back. I felt fine, but desperate for home. They took me to their house, where Amanda was waiting, and I was reunited with a joyful Hazel. She squirmed backwards and forwards in front of my legs, rubbing her bottom against me, twisting her body to look back at me, whining a high pitched squeal.

My reception from the humans had the feeling of fragile celebrity that surrounds the patient who has had a life-changing diagnosis. I think that was the moment when I realised I had entered the realm of the unwell, from which there is no real return. It crossed my mind that I was out of work, an invalid, in the eyes of the world if not in fact, and in the middle of trying to move my mother into a house for us to share. It wasn’t the time to think about these things, though. I wanted to get home.

Prior to my heart attack, I was feeling better about life than I had for some years. I had escaped the bullying supervision of my former “colleague” by an act of economic self-destruction, but I was ready to start looking for alternatives, and the extent to which my mother’s care was going to impact my freedom hadn’t quite hit me. I was volunteering for the cargo bike business, trying to write, with my usual progress, walking the dog, shopping, cooking, reading.

Why did it happen? I truly think that ten years of manipulative bullying by a chaos-queen, on top of my long grief for my father, both before and after his death, had a massive impact on my health. I thought, because I ate a decent vegan diet, had given up smoking and cycled a considerable distance most weeks, that I was immune from the ailments of middle age, but it appears not. The one thing I could not control was my mood of anger and frustration. Some of that was political, but my working life was, for a decade, like a toxic marriage, and I stayed because I needed the money. It had some good aspects, but it was all overshadowed by that fucking person. She has her own challenges and sorrows, but she is a past master at division, manipulation and keeping everyone on the back foot, and herself at the centre of things.

On the other hand, my diet wasn’t perfect, much as I have cooked from scratch for many years. I may have relied upon the bad vegetable fats – coconut and palm – more than I should have and I definitely developed a real instant noodles problem over the last few years. Also, I smoked for thirty years and drank for forty. These things aren’t good.

The genesis of this post was a review of my increasing sorrow: the loss of the optimism that had been my characteristic outlook since my teens. I didn’t notice when I lost my gift for happiness. There wasn’t a moment when I felt a whoosh, a gust of cold and a crushing sense of absence. The jolts to my cheery nature have been cumulative,3 4, rather like my realisation in A&E that what I felt in my chest was serious. I faced each event with the courage it demanded at the time, but, gradually, they eroded me until I had become rather darker than I have been for most of my life, and much sadder.

I’ve been aware of it. I shelled out for counselling for several months last year, and it helped me to confirm my need to ditch the job, and seek more control over my circumstances. And it comes back quite frequently, in moments of understanding, as it did two nights ago, when Amanda and I avoided an argument because, unusually, she let it go.

“You’ve got enough to be dealing with at the moment,” she said. It was dark. We were in the kitchen and I had only put the extractor lights on, so there were shadows surrounding us. I sort of slumped, and she crawled into my arms to hug me.

In her embrace, I remembered that I still have much treasure, a great deal to be grateful for. We will get past this. All will be well.